Good design is a process

Design is, as stated earlier, simply the act of solving problems.

The design profession (all design professions, to be clear) focuses on directing this problem‑solving toward higher chances of success. This requires a repeatable—but customizable—process that can be adapted to many different user needs.

Phase 1: Discovery

Before exploring any solutions, it’s important to understand the problem set from as many angles and perspectives as possible. The better our understanding of the problem space, the more likely our solutions to be more holistic and solve more aspects of the problem.

Simple challenges

Simple or clearly defined challenges, such as addressing customer complaints about placement of the “checkout” button, can consist of:

Stakeholder discussions/interviews

Review of analytics/data

Heuristic evaluation

A/B testing

Stakes and effort tend to be low. Missteps tend to be quick to adjust and can be mitigated by A/B testing after launch.

Complex challenges

For complicated challenges with many unknowns, such as defining the purchasing flow for a health insurance product, a more holistic approach is necessary and can include:

Collaborative stakeholder alignment workshops

Qualitative interviews with user

Quantitative surveys

Experience roadmaps

Contextual observation

And many other Human-Centered Design methods

Stakes and effort are typically high. Not fully understanding the users’ journey and intent can lead to a failure of an entire product to effectively enter the market.

Having a thorough definition of the challenges to be solved helps to define the scope and goals of the work while prioritizing must be kept and what can be sacrificed during the production lifecycle.

Phase 2: Conceptualization

Solving the challenges defined with the Discovery phase has its own set of obstacles. What may seem like an obvious approach may leave opportunities on the table.

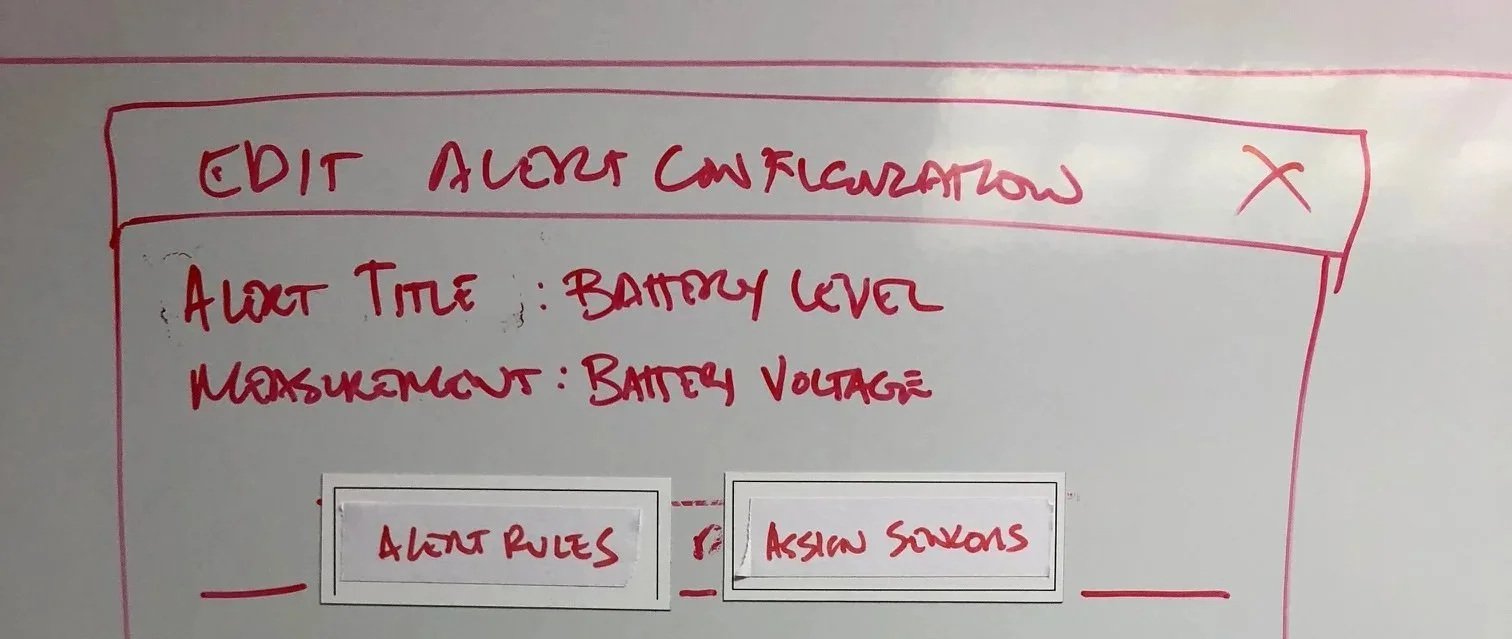

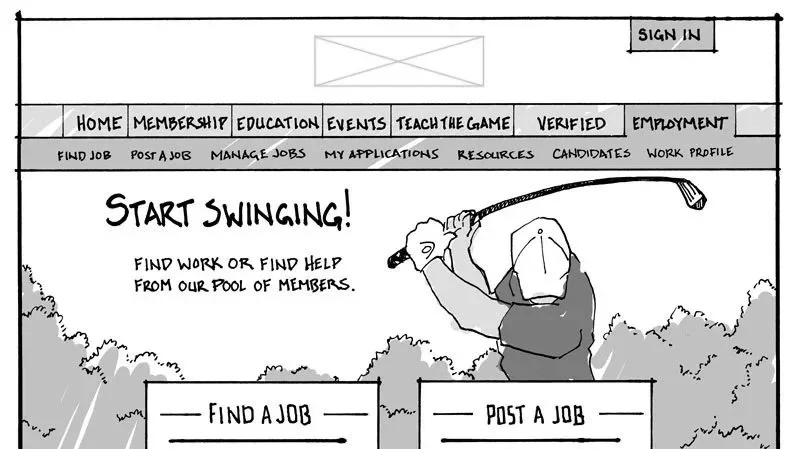

Brainstorming/Sketching

Brainstorming and loose sketching lets us quickly explore different approaches to solving the challenges ahead of us. These quick studies can help us assess various concepts for feasibility without having to spend too much time or resources. Every design profession incorporates some level of low-fidelity exploration, and digital design is no different.

Wireframing

As the quick conceptual explorations start to point in a more solid direction, the artifacts we create often also solidify. Wireframes are similar to architectural blueprints where the parts of the experience start to get defined, but visual style and color are as yet ignored. Typically, these blueprints are used to block out the experience to obtain feedback. Within some processes, wireframes can be used for immediate prototyping, either using design tools or working directly with developers. Part of this process is also understanding the overall flow and external impacts, so an information architecture diagram may serve as the backbone of the wireframes.

These rough concepts can be tested and vetted with stakeholders and users to get a better indication of whether the solution is headed down the right path. Multiple rounds can be implemented depending on time and resources.

Phase 3: Production

Production typically consists of finishing the design and handing the work off to developers for programming. There are two main schools of production that are typically leveraged based on the circumstance. Though hybrids of the two do exist, there are often drawbacks.

Waterfall

Waterfall is a traditional production process that relies on the designer to fully flesh out and complete pixel-perfect visual comps that are then handed off to the development team (or the next part of the process). Thorough QA is recommended at every milestone so that the next part of the process doesn’t adopt errors.

Typically, this process is recommended for very straightforward, simple experiences such as a content-focused web page with limited calls to action and minimal conditional logic.

Agile

Agile, a process originating from Toyota and the car manufacturing world, leverages a series of iterative sprints in order to accommodate ambiguity in the criteria for success. Cross-functional teams work hand in hand to define and execute on small parts of the experience, testing and improving along the way. The individual components are then stitched together along the way until the work is completed, typically to the level of a minimum viable product. Work can then continue to improve and add features as needed.

This is recommended for high complexity experiences with a lot of edge cases and error states.

No matter the production process, it’s important for the designer(s) to stay engaged with the work as it’s being developed. Actively collaborating with the development team is essential to successful output. Ownership of the final product should be shared by all the stakeholders, together.

Phase 4: Quality assurance

To ensure the integrity of the experience, thorough testing to find bugs and edge cases should be done so that the end users’ experience is as smooth as possible with adequate escape routes and error handling.

Phase 5: Launch

Once all the bugs have been hammered out (or release noted), the experience is ready for launch. However, the work doesn’t necessarily end there. Data and analytics should be captured to ensure that opportunities for improvement in future iterations can be analyzed.